The Twelve Minute Shiur

Byte-size learning from the Freehof Institute

Download the audio and the source sheet for each shiur

Byte-size learning from the Freehof Institute

Download the audio and the source sheet for each shiur

#59 - Yom Tov Sheni, Part 2

Source Sheet

More on the second festival day, like: why do many Jews still observe it when we no longer have any doubt as to the right date of yom tov? And what about the second day of Rosh Hashanah? It looks, smells, and quacks just like a regular yom tov sheni... but it's not!

Source Sheet

More on the second festival day, like: why do many Jews still observe it when we no longer have any doubt as to the right date of yom tov? And what about the second day of Rosh Hashanah? It looks, smells, and quacks just like a regular yom tov sheni... but it's not!

#58 - Yom Tov Sheni, Part 1

Source Sheet

Why do many Jews outside of Eretz Yisrael turn every Biblically-ordained festival day (yom tov) into a two-day observance? What's the nature of that second day, especially since we no longer have any uncertainty about determining the months and the dates of the Jewish calendar? And why do progressive Jews dispense with the observance of yom tov sheni altogether? Lots of questions, and we'll try to answer them, beginning with this installment. Warning: some of the answers may surprise you!

Source Sheet

Why do many Jews outside of Eretz Yisrael turn every Biblically-ordained festival day (yom tov) into a two-day observance? What's the nature of that second day, especially since we no longer have any uncertainty about determining the months and the dates of the Jewish calendar? And why do progressive Jews dispense with the observance of yom tov sheni altogether? Lots of questions, and we'll try to answer them, beginning with this installment. Warning: some of the answers may surprise you!

#57 - May a Blind Person Be Called to the Torah?

Source Sheet

Rabbi Yosef Caro, in his Shulhan Arukh, holds that a blind person may not be called up to the Torah. That ruling stirred a halakhist of the next generation, Rabbi Binyamin Selonik, to write a responsum that holds the opposite. Just your ordinary, run-of-the-mill halakhic mahloket - except that Rabbi Selonik himself was blind, a reality he emphasizes explicitly and passionately in his text, making sure that we read the sources through the eyes of one who - if the Shulhan Arukh is right - would be excluded from participation in a beloved mitzvah.

Source Sheet

Rabbi Yosef Caro, in his Shulhan Arukh, holds that a blind person may not be called up to the Torah. That ruling stirred a halakhist of the next generation, Rabbi Binyamin Selonik, to write a responsum that holds the opposite. Just your ordinary, run-of-the-mill halakhic mahloket - except that Rabbi Selonik himself was blind, a reality he emphasizes explicitly and passionately in his text, making sure that we read the sources through the eyes of one who - if the Shulhan Arukh is right - would be excluded from participation in a beloved mitzvah.

#56 - Thinking Halakhicly About Disability

Source Sheet

In halakhah, as in life, there are two ways - one "passive," the other "active" - to think about disability and of our response to it. In this episode, we consider examples of each.

Source Sheet

In halakhah, as in life, there are two ways - one "passive," the other "active" - to think about disability and of our response to it. In this episode, we consider examples of each.

#55 - Who Is Worthy to Lead Us in Prayer? Part 2

Source Sheet

Picking up where we left off in episode #53. What qualities should we want in a shaliach tzibur (prayer leader)? And what qualities are we best advised to avoid? The halakhah weighs in.

Source Sheet

Picking up where we left off in episode #53. What qualities should we want in a shaliach tzibur (prayer leader)? And what qualities are we best advised to avoid? The halakhah weighs in.

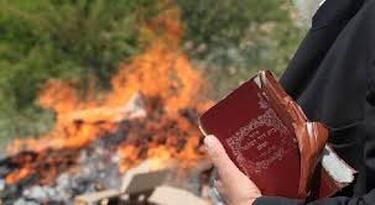

#54 - Getting Rid of Hametz

Source Sheet

Pesach is coming. Time to get rid of your hametz. And there are four different ways to do it. Oh, the choices! This episode explores the whys and the hows.

For more on this topic see our essay Bi’ur, M’khirah, or Bitul? On Getting Rid of Hametz

Source Sheet

Pesach is coming. Time to get rid of your hametz. And there are four different ways to do it. Oh, the choices! This episode explores the whys and the hows.

For more on this topic see our essay Bi’ur, M’khirah, or Bitul? On Getting Rid of Hametz

|

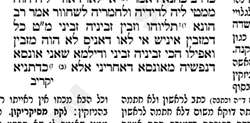

#53 - Who Is Worthy to Lead Us in Prayer? Part 1

Source Sheet The leader of the prayer service - the shaliach tzibur - is traditionally considered our representative or emissary before God. So it's understandable that we want to appoint the very best person, or at least someone who is worthy for that job. Okay... but how do we define "worthy"? The first of a two-part series. |

#52 - "They Teach Him the Principles of the Faith":

Is Rambam Just Making This Up?

Source Sheet

For nearly a thousand years, students of the Mishneh Torah, Rambam's great code of halakhah, have sought to identify the Talmudic sources of his rulings. Sometimes, he appears to have no source whatsoever. When this happens, we have to ask: is Rambam just making this up? Is it permissible even for a great posek to derive a rule of halakhah on the basis of common sense or of his personal judgment? In this installment, we look at two outstanding commentators with two very different answers to that question.

Is Rambam Just Making This Up?

Source Sheet

For nearly a thousand years, students of the Mishneh Torah, Rambam's great code of halakhah, have sought to identify the Talmudic sources of his rulings. Sometimes, he appears to have no source whatsoever. When this happens, we have to ask: is Rambam just making this up? Is it permissible even for a great posek to derive a rule of halakhah on the basis of common sense or of his personal judgment? In this installment, we look at two outstanding commentators with two very different answers to that question.

#51 - B'rakhot: Is It Okay to Change the Text?

Source Sheet

Progressive Jews have been writing new texts for the b'rakhot, the blessings or benedictions that form the core of our worship, for just about 200 years. There are lots of reasons why we'd want to do that, but our question here is whether we violate halakhah when we do it. Does Jewish law permit us to alter the text - the nusach - of a liturgical form that according to tradition was ordained by the ancient Rabbis and perhaps even by Ezra the scribe? We have a theory that says "yes."

For more on this topic, see our essay "On Changing the Text of B'rakhot"

CCAR Responsum 5763.6, "Matriarchs in the T'filah"

CJLS OH 112.1990, "Regarding the Inclusion of the Names of the Matriarchs in the First Blessing of the עמידה"

Source Sheet

Progressive Jews have been writing new texts for the b'rakhot, the blessings or benedictions that form the core of our worship, for just about 200 years. There are lots of reasons why we'd want to do that, but our question here is whether we violate halakhah when we do it. Does Jewish law permit us to alter the text - the nusach - of a liturgical form that according to tradition was ordained by the ancient Rabbis and perhaps even by Ezra the scribe? We have a theory that says "yes."

For more on this topic, see our essay "On Changing the Text of B'rakhot"

CCAR Responsum 5763.6, "Matriarchs in the T'filah"

CJLS OH 112.1990, "Regarding the Inclusion of the Names of the Matriarchs in the First Blessing of the עמידה"

#50 - Why Are We Still Saying Kiddush in the Synagogue?

Source Sheet

We ask that the congregation please rise... to observe a custom (minhag) that was created for a very specific reason. That reason disappeared over 1000 years ago. So what did the Jews do about that? You guessed it: they maintained the minhag and came up with new reasons for it. That in itself tells us something about the role of minhag in our religious life. And as for those new reasons, do they have anything to teach us? Well, just maybe.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Why Are We Still Saying Kiddush in the Synagogue?"

Source Sheet

We ask that the congregation please rise... to observe a custom (minhag) that was created for a very specific reason. That reason disappeared over 1000 years ago. So what did the Jews do about that? You guessed it: they maintained the minhag and came up with new reasons for it. That in itself tells us something about the role of minhag in our religious life. And as for those new reasons, do they have anything to teach us? Well, just maybe.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Why Are We Still Saying Kiddush in the Synagogue?"

#49 - The Death of King Saul and Physician-Assisted Suicide

Source Sheet

It's one of the most famous cases of suicide in all of Jewish literature. Saul, king of Israel, falls on his sword in order to avoid being taken alive and abused by the Philistines. Does this story serve as a precedent in support of physician-assisted suicide in cases of terminal illness? Some say yes. But (and you saw this coming, didn't you?) it's complicated.

For more on this topic, see:

CCAR Responsum 5783.1 Medical Assistance in Dying

Committee on Jewish Law and Standards YD 345.1997c Assisted Suicide/Aid in Dying Reconsidered

Freehof Institute A Note on Medical Assistance in Dying (Physician-Assisted Suicide)

Source Sheet

It's one of the most famous cases of suicide in all of Jewish literature. Saul, king of Israel, falls on his sword in order to avoid being taken alive and abused by the Philistines. Does this story serve as a precedent in support of physician-assisted suicide in cases of terminal illness? Some say yes. But (and you saw this coming, didn't you?) it's complicated.

For more on this topic, see:

CCAR Responsum 5783.1 Medical Assistance in Dying

Committee on Jewish Law and Standards YD 345.1997c Assisted Suicide/Aid in Dying Reconsidered

Freehof Institute A Note on Medical Assistance in Dying (Physician-Assisted Suicide)

#48 - On the Flexibility of the Halakhah

Source Sheet

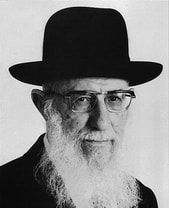

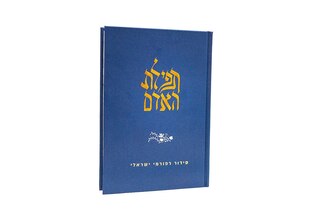

At the Freehof Institute, we understand halakhah in its best sense not as a set of fixed rules but as a discourse, a language of thought and of argument that Jews utilize to study their sacred sources and determine just what they tell us when it comes to matters of sacred action. And we believe that language to be a flexible one, a process that can yield guidance fully coherent with our own liberal and progressive religious outlook. We certainly don’t believe that Rabbi Hayyim David Halevi (d. 1998; that’s him to the right), the S’fardic chief rabbi of Tel Aviv-Yafo, qualifies as a liberal or a progressive. But when it comes to the “flexibility of the halakhah,” a phrase that he invented, well, we like to think that he and we are working from the same playbook.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Rabbi Hayyim David Halevy on 'Innovations' in Jewish Law"

Source Sheet

At the Freehof Institute, we understand halakhah in its best sense not as a set of fixed rules but as a discourse, a language of thought and of argument that Jews utilize to study their sacred sources and determine just what they tell us when it comes to matters of sacred action. And we believe that language to be a flexible one, a process that can yield guidance fully coherent with our own liberal and progressive religious outlook. We certainly don’t believe that Rabbi Hayyim David Halevi (d. 1998; that’s him to the right), the S’fardic chief rabbi of Tel Aviv-Yafo, qualifies as a liberal or a progressive. But when it comes to the “flexibility of the halakhah,” a phrase that he invented, well, we like to think that he and we are working from the same playbook.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Rabbi Hayyim David Halevy on 'Innovations' in Jewish Law"

#47 - What's Wrong with the Electric Hanukkiah?

Source Sheet

According to halakhah, can you fulfill the mitzvah of Hanukkah, the lighting of the Hanukkah lamp, by using electric lights? Most Orthodox authorities say "no." We say "yes," and here's why.

For more on this topic, see our essay "A Note on the Electric Hanukkiah"

Source Sheet

According to halakhah, can you fulfill the mitzvah of Hanukkah, the lighting of the Hanukkah lamp, by using electric lights? Most Orthodox authorities say "no." We say "yes," and here's why.

For more on this topic, see our essay "A Note on the Electric Hanukkiah"

|

#46 - Deception Part 2

Source Sheet Back in shiur #44 we saw that a great posek (well, it's Rambam, so maybe the greatest posek) writes as though the prohibition against g'neivat da`at, deceptive speech and behavior, is absolute, admitting of no exceptions. If so, then he agrees with the great philosopher Immanuel Kant and contradicts some clear statements in the Talmud. What's going on here? We have some ideas. |

#45 - On the Halakhah of War

Source Sheet

Does Jewish law distinguish between "just" and "unjust" wars? And what duties do we owe to noncombatant populations during wartime? This episode was recorded in October 2023, when these subjects suddenly and sadly became relevant for Israel and the entire Jewish people.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Just” Wars, “Unjust” Wars, and the Treatment of Noncombatants in Wartime

Source Sheet

Does Jewish law distinguish between "just" and "unjust" wars? And what duties do we owe to noncombatant populations during wartime? This episode was recorded in October 2023, when these subjects suddenly and sadly became relevant for Israel and the entire Jewish people.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Just” Wars, “Unjust” Wars, and the Treatment of Noncombatants in Wartime

#44 - Deception: Creating a False Impression

Source Sheet

It's no surprise that the halakhah frowns upon deceptive behavior (g'neivat da`at). We are forbidden to act in such a way as to create a false impression in the minds of others, even when our action causes them no material loss, simply because deception in and of itself is a bad thing. But how bad is it? Are we always forbidden to deceive? Without exception?

Well, there's a machloket about that.

Source Sheet

It's no surprise that the halakhah frowns upon deceptive behavior (g'neivat da`at). We are forbidden to act in such a way as to create a false impression in the minds of others, even when our action causes them no material loss, simply because deception in and of itself is a bad thing. But how bad is it? Are we always forbidden to deceive? Without exception?

Well, there's a machloket about that.

#43 - Kol Nidre: Timing Is Everything

Source Sheet

Des your community recite Kol Nidre before or after sundown at the beginning of Yom Kippur? Does it matter? In a word... yes, because either way, you're making a statement. What statement is that? Glad you asked - do we have a shiur for you!

Source Sheet

Des your community recite Kol Nidre before or after sundown at the beginning of Yom Kippur? Does it matter? In a word... yes, because either way, you're making a statement. What statement is that? Glad you asked - do we have a shiur for you!

#42 – Avinu Malkeinu on Shabbat

Source Sheet

Avinu Malkeinu - it's one of the most dramatic and powerful moments in the High Holiday liturgy. "Traditional" congregations omit this dramatic and powerful prayer on Shabbat, while Reform congregations recite it. Who's right? Well, you'll never believe this, but... it's a maḥloket! The Jews disagree among themselves - imagine that! In this installment, we'll explore the arguments of those who think that Avinu Malkeinu is inappropriate on Shabbat, and we'll consider why other communities are not persuaded by those arguments.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Avinu Malkeinu on Shabbat"

Source Sheet

Avinu Malkeinu - it's one of the most dramatic and powerful moments in the High Holiday liturgy. "Traditional" congregations omit this dramatic and powerful prayer on Shabbat, while Reform congregations recite it. Who's right? Well, you'll never believe this, but... it's a maḥloket! The Jews disagree among themselves - imagine that! In this installment, we'll explore the arguments of those who think that Avinu Malkeinu is inappropriate on Shabbat, and we'll consider why other communities are not persuaded by those arguments.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Avinu Malkeinu on Shabbat"

#41 – The Shofar on Shabbat

Source Sheet

It's almost 5784! This year, Rosh Hashanah falls on Shabbat, and Reform congregations will sound the shofar on that day. They do so because they observe only one day of the yom tov rather than the traditional two. They do so also because the halakhah supports their practice. Wait - what?? Doesn't the halakhah prohibit sounding the shofar on Shabbat? Well, there's actually a maḥloket over that, and in this installment we'll consider why the Reform practice conforms to the better side of the dispute.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Sounding The Shofar on Shabbat "

Source Sheet

It's almost 5784! This year, Rosh Hashanah falls on Shabbat, and Reform congregations will sound the shofar on that day. They do so because they observe only one day of the yom tov rather than the traditional two. They do so also because the halakhah supports their practice. Wait - what?? Doesn't the halakhah prohibit sounding the shofar on Shabbat? Well, there's actually a maḥloket over that, and in this installment we'll consider why the Reform practice conforms to the better side of the dispute.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Sounding The Shofar on Shabbat "

#40 – When Halakhah and Ethics Collide, Part 3

Source Sheet

In our previous installment, we saw how the Rabbis utilized the power of property confiscation (hefker beit din) as a way to repair inequities they perceived in the law of the Torah. In this shiur, we'll look at how that power enabled them to correct some glaring economic imbalances in the institution of marriage as the Torah defines it. In the process, they restructured that institution in a fundamental way.

Source Sheet

In our previous installment, we saw how the Rabbis utilized the power of property confiscation (hefker beit din) as a way to repair inequities they perceived in the law of the Torah. In this shiur, we'll look at how that power enabled them to correct some glaring economic imbalances in the institution of marriage as the Torah defines it. In the process, they restructured that institution in a fundamental way.

#39 – When Halakhah and Ethics Collide, Part 2

Source Sheet

In our last installment, we looked at one way in which the Rabbis respond when they perceive that a mitzvah of the Torah or a rule of halakhah conflicts with accepted standards of ethics and justice: the way of story. The Rabbis, that is, create new narratives to offer context and explanation to the rule, showing that in fact it does not violate our sense of right and wrong. In this installment, the Rabbis take a more direct approach: they adopt legislation of their own to correct that faults they find in the Torah law. And we'll consider just how they have the temerity to imagine they have the power to do that!

Source Sheet

In our last installment, we looked at one way in which the Rabbis respond when they perceive that a mitzvah of the Torah or a rule of halakhah conflicts with accepted standards of ethics and justice: the way of story. The Rabbis, that is, create new narratives to offer context and explanation to the rule, showing that in fact it does not violate our sense of right and wrong. In this installment, the Rabbis take a more direct approach: they adopt legislation of their own to correct that faults they find in the Torah law. And we'll consider just how they have the temerity to imagine they have the power to do that!

#38 – When Halakhah and Ethics Collide, Part 1

Source Sheet

How do we respond when we discover that a mitzvah of the Torah or a rule of halakhah conflicts with our sense of ethics and justice? For some, that's not a problem at all: since the Torah is always right, our sense of ethics and justice must be wrong or distorted. We liberal and progressive Jews, of course, see things differently. And as a matter of fact, so do the Rabbis of the halakhic tradition. When they confront such a conflict, they don't pretend that it doesn't exist, nor do they simply reject ethics to exalt Torah. Instead, they seek to understand the halakhah in light of the standards of ethics and justice that they regard as right and proper. This installment is the first in a series exploring some ways in which the Rabbis reach that understanding, some ways in which they respond when halakhah and ethics collide.

Source Sheet

How do we respond when we discover that a mitzvah of the Torah or a rule of halakhah conflicts with our sense of ethics and justice? For some, that's not a problem at all: since the Torah is always right, our sense of ethics and justice must be wrong or distorted. We liberal and progressive Jews, of course, see things differently. And as a matter of fact, so do the Rabbis of the halakhic tradition. When they confront such a conflict, they don't pretend that it doesn't exist, nor do they simply reject ethics to exalt Torah. Instead, they seek to understand the halakhah in light of the standards of ethics and justice that they regard as right and proper. This installment is the first in a series exploring some ways in which the Rabbis reach that understanding, some ways in which they respond when halakhah and ethics collide.

#37 - Jewish Law: The Quiet Revolution

Source Sheet

In theory, Jewish law judges must be ordained for that role. They must possess s'mikhah from a judge who is already ordained (samukh), forming a link in the teacher-to-student chain that stretches all the way back to Moses and Joshua. But s’mikhah, which could take place only in Eretz Yisrael, was discontinued some 1000 years ago (today's rabbinical ordination, purely symbolic, is not the same thing). So how can Jewish law function in a world quite different from the one envisioned in our ancient texts? The answer: the scholars of the Diaspora simply seized judicial power for themselves. That qualifies as a revolution, but like the good halakhic scholars they were, they made sure to disguise the revolutionary nature of their action.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Jewish Law: The Quiet Revolution"

Source Sheet

In theory, Jewish law judges must be ordained for that role. They must possess s'mikhah from a judge who is already ordained (samukh), forming a link in the teacher-to-student chain that stretches all the way back to Moses and Joshua. But s’mikhah, which could take place only in Eretz Yisrael, was discontinued some 1000 years ago (today's rabbinical ordination, purely symbolic, is not the same thing). So how can Jewish law function in a world quite different from the one envisioned in our ancient texts? The answer: the scholars of the Diaspora simply seized judicial power for themselves. That qualifies as a revolution, but like the good halakhic scholars they were, they made sure to disguise the revolutionary nature of their action.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Jewish Law: The Quiet Revolution"

#36 - The Mitzvah of Matzah: One Day or Seven?

Source Sheet

The official, codified halakhah says that we are obligated to eat matzah only one day, the first night of Pesach at the seder. But there's another tradition that understands the mitzvah of matzah to last for all seven days of the festival. This is no ordinary maḥloket among the Rabbis but a full-blown critique of the codified halakhah by scholars who find that official version to be spiritually insufficient and contradictory of the purpose of the mitzvah. We have here, in other words, a pretty good example of progressive halakhic thinking... by poskim whom we don't normally think of as "progressive!"

For more on this topic, see our essay "Is Matzah a Mitzvah for All Seven Days of Pesach?"

Source Sheet

The official, codified halakhah says that we are obligated to eat matzah only one day, the first night of Pesach at the seder. But there's another tradition that understands the mitzvah of matzah to last for all seven days of the festival. This is no ordinary maḥloket among the Rabbis but a full-blown critique of the codified halakhah by scholars who find that official version to be spiritually insufficient and contradictory of the purpose of the mitzvah. We have here, in other words, a pretty good example of progressive halakhic thinking... by poskim whom we don't normally think of as "progressive!"

For more on this topic, see our essay "Is Matzah a Mitzvah for All Seven Days of Pesach?"

#35 – Why Don’t We Pray for Rain When We Actually Need the Rain? Part 2

Source Sheet

We conclude out two-part series on birkat hashanim with a look at how one leading medieval sage makes a powerful argument in favor of allowing the Jews of all lands to pray for rain when they need it, during the rainy season in their countries. True, his argument was not accepted by the majority, but it sure makes sense to us.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Praying for Rain - When?"

Source Sheet

We conclude out two-part series on birkat hashanim with a look at how one leading medieval sage makes a powerful argument in favor of allowing the Jews of all lands to pray for rain when they need it, during the rainy season in their countries. True, his argument was not accepted by the majority, but it sure makes sense to us.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Praying for Rain - When?"

#34 – Why Don’t We Pray for Rain When We Actually Need the Rain? Part 1

Source Sheet

It's springtime! And we just stopped praying for rain in the t'filah, even though many of us live in places where we need the rain during this time of year. Why is that? Because the Jews in the entire Diaspora are required to behave as though they live in ancient Babylonia. Is there a fix for this? You bet there is, and it isn't our idea: some high-profile rishonim beat us to it. Now if somebody would only listen to them.

For more on this topic, see our essay "Praying for Rain - When?"

#33 – The Four Questions (?)

Source Sheet

In this installment, we have some questions about the Four Questions. Like: are they really questions at all? And: are there really four of them? Join us for this look at one of everybody's favorite moments at the seder.

Source Sheet

In this installment, we have some questions about the Four Questions. Like: are they really questions at all? And: are there really four of them? Join us for this look at one of everybody's favorite moments at the seder.

#32 – Is Medical Treatment Compulsory?

Source Sheet

The halakhah teaches that the practice of medicine (r'fu'ah) partakes of the mitzvah of pikuach nefesh, the saving of human life. That's a moral obligation that overrides virtually any other mitzvah that might get in the way. If so, is medical treatment compulsory? Does Jewish law mandate that we always follow the instructions of the physicians? Like most interesting questions of halakhah, this one is complicated. In this episode, we explore that complexity.

For more on this topic, see our essays:

Source Sheet

The halakhah teaches that the practice of medicine (r'fu'ah) partakes of the mitzvah of pikuach nefesh, the saving of human life. That's a moral obligation that overrides virtually any other mitzvah that might get in the way. If so, is medical treatment compulsory? Does Jewish law mandate that we always follow the instructions of the physicians? Like most interesting questions of halakhah, this one is complicated. In this episode, we explore that complexity.

For more on this topic, see our essays:

#31 - Adloyada - Really??

Source Sheet

It's one of the strangest of all halakhic rules: "one is obligated to become intoxicated with wine on Purim to the point that one cannot tell the difference between 'cursed be Haman' and 'blessed be Mordekhai.'” Read literally, this is a requirement that we celebrate the joy of Purim by getting ourselves wasted, stinking drunk, which is hardly in keeping with almost everything else the tradition teaches us. So... must we read it literally? In this installment, we'll look at a number of authorities who don't. Which, of course, raises some interesting questions about the nature of halakhic interpretation.

For More on this topic, see our essay "Is It Really a Mitzvah to Get Drunk on Purim? Adloyada and Progressive Halakhah"

Source Sheet

It's one of the strangest of all halakhic rules: "one is obligated to become intoxicated with wine on Purim to the point that one cannot tell the difference between 'cursed be Haman' and 'blessed be Mordekhai.'” Read literally, this is a requirement that we celebrate the joy of Purim by getting ourselves wasted, stinking drunk, which is hardly in keeping with almost everything else the tradition teaches us. So... must we read it literally? In this installment, we'll look at a number of authorities who don't. Which, of course, raises some interesting questions about the nature of halakhic interpretation.

For More on this topic, see our essay "Is It Really a Mitzvah to Get Drunk on Purim? Adloyada and Progressive Halakhah"

#30 - When Doctors Do Harm: Medical Malpractice in the Halakhah, Part 2

Source Sheet

In installment #29, we saw how the halakhah, as expressed by some major rishonim and the leading codes, tends to protect the physician from claims for damages due to negligence in medical treatment. Well, it turns out that there's a different trend in halakhic thinking that holds doctors liable for those damages. It's the other side of the halakhah of malpractice.

Source Sheet

In installment #29, we saw how the halakhah, as expressed by some major rishonim and the leading codes, tends to protect the physician from claims for damages due to negligence in medical treatment. Well, it turns out that there's a different trend in halakhic thinking that holds doctors liable for those damages. It's the other side of the halakhah of malpractice.

#29 – When Doctors Do Harm: Medical Malpractice in the Halakhah, Part 1

Source Sheet

In the previous two shiurim, we've seen that the practice of medicine (r'fu'ah) is defined as a mitzvah. It's holy work, a duty the physician owes to the patient. But if so, does halakhah exempt the physician from liability for causing injury (or worse) in the course of treatment? It's a complex question, and we begin its exploration in this installment.

Source Sheet

In the previous two shiurim, we've seen that the practice of medicine (r'fu'ah) is defined as a mitzvah. It's holy work, a duty the physician owes to the patient. But if so, does halakhah exempt the physician from liability for causing injury (or worse) in the course of treatment? It's a complex question, and we begin its exploration in this installment.

#28 – The Mitzvah of Medicine, Part 2

Source Sheet

In our last installment, we saw how Ramban (Nachmanides) created a theory to prove that the practice of medicine is a mitzvah. In this shiur, we consider a different theory, that of Rambam (Maimonides). Since both these giant rishonim reach the same conclusion, is there a nafka minah, a practical difference between them? We think that maybe - just maybe - there is.

Source Sheet

In our last installment, we saw how Ramban (Nachmanides) created a theory to prove that the practice of medicine is a mitzvah. In this shiur, we consider a different theory, that of Rambam (Maimonides). Since both these giant rishonim reach the same conclusion, is there a nafka minah, a practical difference between them? We think that maybe - just maybe - there is.

#27 – The Mitzvah of Medicine, Part 1

Source Sheet

The first in a series of shiurim devoted to the nature of medicine as understood in the halakhah. It's a mitzvah to practice medicine, to heal the sick, right? Sure it is; the Shulchan Arukh says so explicitly. But as always, we have to ask that pesky Rabbinic question: how do we know this? In this case, it's Ramban (Nachmanides) to the rescue.

Source Sheet

The first in a series of shiurim devoted to the nature of medicine as understood in the halakhah. It's a mitzvah to practice medicine, to heal the sick, right? Sure it is; the Shulchan Arukh says so explicitly. But as always, we have to ask that pesky Rabbinic question: how do we know this? In this case, it's Ramban (Nachmanides) to the rescue.

#26 – What Is Prayer? A Follow-Up

Source Sheet

In our previous shiur, we saw that Rambam regards the mitzvah of t'filah as d'oraita: that is, the Torah itself instructs us to pray once a day. So how does he think we got from that to the three- (or four-) times daily regimen of t'filot traditionally recited today?

Source Sheet

In our previous shiur, we saw that Rambam regards the mitzvah of t'filah as d'oraita: that is, the Torah itself instructs us to pray once a day. So how does he think we got from that to the three- (or four-) times daily regimen of t'filot traditionally recited today?

#25 – What Is Prayer? And Why Is That Such a Hard Question?

Source Sheet

In this installment, we take a look at an old maḥloket between two halakhic giants - Rambam (Maimonides) and Ramban (Nachmanides) - over the status, the origin, and the function of prayer according to the tradition of the halakhah. That's why it's a hard question. Who has the better argument? Well, that's a hard question, too, but there's a lot we can learn from both sides.

Source Sheet

In this installment, we take a look at an old maḥloket between two halakhic giants - Rambam (Maimonides) and Ramban (Nachmanides) - over the status, the origin, and the function of prayer according to the tradition of the halakhah. That's why it's a hard question. Who has the better argument? Well, that's a hard question, too, but there's a lot we can learn from both sides.

|

#24 – Should Jews Celebrate Thanksgiving?

Source Sheet Thanksgiving is a beloved (if non-Jewish) holiday for American Jews. So why did the eminent Orthodox posek R. Moshe Feinstein rule that they shouldn't celebrate it? In this installment, we study his argument... and the reason that progressive halakhah disagrees. |

#23 – Halakhah and the Regulation of Firearms, Part 2

Source Sheet In this installment, we read a second responsum of Rabbi Hayyim David Halevy on firearms control. This one fleshes out his thinking on the subject. How does halakhah want us to think, talk, and argue about this issue in the public sphere? |

#22 – Halakhah and the Regulation of Firearms, Part 1

Source Sheet

Does Jewish law offer any useful guidance to societies facing the issue of the control and regulation of firearms? In this installment and the next, we explore that question by studying two responsa of Rabbi Hayyim David Halevy, who at his death in 1998 served as chief S'fardic rabbi of Tel-Aviv-Yafo.

Source Sheet

Does Jewish law offer any useful guidance to societies facing the issue of the control and regulation of firearms? In this installment and the next, we explore that question by studying two responsa of Rabbi Hayyim David Halevy, who at his death in 1998 served as chief S'fardic rabbi of Tel-Aviv-Yafo.

#21 – The Sukkah – Why Size Matters

Source Sheet

Not too tall, not too small. Among other things, it's about humility.

Source Sheet

Not too tall, not too small. Among other things, it's about humility.

#20 – Pikuach Nefesh on Yom Kippur: Loading the Dice

Source Sheet

In deciding whether to break one's fast on Yom Kippur, as with other medical issues, the halakhah tells us to follow the counsel of experts. Except when it doesn't. In this episode we explore how the halakhah makes sure that we always err on the side of life.

Source Sheet

In deciding whether to break one's fast on Yom Kippur, as with other medical issues, the halakhah tells us to follow the counsel of experts. Except when it doesn't. In this episode we explore how the halakhah makes sure that we always err on the side of life.

#19 – Patriotism and the Halakhah, Part 2

Source Sheet

In our last installment, we were left with the question: does Jewish law recognize that we bear a duty of patriotism? Does it oblige us to care for the country in which we live, to work for its welfare, to defend it against attack? In this shiur, we suggest a halakhic basis for patriotism, at least for citizens of democratic societies: the principle of dina d'malkhuta dina, “the law of the state is valid law,” acknowledged as such by Jewish legal tradition.

Source Sheet

In our last installment, we were left with the question: does Jewish law recognize that we bear a duty of patriotism? Does it oblige us to care for the country in which we live, to work for its welfare, to defend it against attack? In this shiur, we suggest a halakhic basis for patriotism, at least for citizens of democratic societies: the principle of dina d'malkhuta dina, “the law of the state is valid law,” acknowledged as such by Jewish legal tradition.

#18 – Patriotism and the Halakhah, Part 1

Source Sheet

Is it appropriate for a synagogue to display the national flag on its bimah? Does this exalt the flag to the status of Jewish religious symbol? Does this differ from the prayers that Jews have for centuries recited for the welfare of the king/queen/government? And for that matter, does halakhah have anything to say about "patriotism," devotion to the wellbeing of one's country? We definitely won't cover all of that in twelve minutes, but we'll make a start!

Source Sheet

Is it appropriate for a synagogue to display the national flag on its bimah? Does this exalt the flag to the status of Jewish religious symbol? Does this differ from the prayers that Jews have for centuries recited for the welfare of the king/queen/government? And for that matter, does halakhah have anything to say about "patriotism," devotion to the wellbeing of one's country? We definitely won't cover all of that in twelve minutes, but we'll make a start!

#17 – Happy the Elephant and the Halakhah

Source Sheet

Happy is an elephant living at the Bronx Zoo. She was the subject of a recent court case that dealt with the question: what legal rights - if any - does an animal enjoy? And this got us thinking, naturally, about what Jewish law might have to say about the same question.

For more on this topic, see our essay On Animal "Rights"

Source Sheet

Happy is an elephant living at the Bronx Zoo. She was the subject of a recent court case that dealt with the question: what legal rights - if any - does an animal enjoy? And this got us thinking, naturally, about what Jewish law might have to say about the same question.

For more on this topic, see our essay On Animal "Rights"

#16 – Coercion and Tzedakah

Source Sheet

In our last few installments, we’ve been talking about the interplay of coercion and consent in the halakhah. In this shi`ur, we’ll take a look at the mitzvah of tz’dakah. It’s a mitzvah that, in theory, the community does not have the power to enforce. The Rabbis, however, were not satisfied with that state of affairs.

Source Sheet

In our last few installments, we’ve been talking about the interplay of coercion and consent in the halakhah. In this shi`ur, we’ll take a look at the mitzvah of tz’dakah. It’s a mitzvah that, in theory, the community does not have the power to enforce. The Rabbis, however, were not satisfied with that state of affairs.

#15 – Coercion, Consent, Marriage and Divorce

Source Sheet

Our last two episodes have dealt with the interplay of coercion and consent in the halakhah: how is it possible that I can be coerced into giving my free-will consent to a legal transaction? This episode explores how coercion, both legal and physical, plays a vital role in the traditional Jewish law of marriage and divorce. We’ll find that coercion may be distasteful, but sometimes it’s the best and surest way to achieve justice, particularly for women, who suffer significant legal disadvantages under that system.

Source Sheet

Our last two episodes have dealt with the interplay of coercion and consent in the halakhah: how is it possible that I can be coerced into giving my free-will consent to a legal transaction? This episode explores how coercion, both legal and physical, plays a vital role in the traditional Jewish law of marriage and divorce. We’ll find that coercion may be distasteful, but sometimes it’s the best and surest way to achieve justice, particularly for women, who suffer significant legal disadvantages under that system.

#14 – Coercion and Consent, Part 2

Source Sheet

"If they hang him from a tree until he agrees to sell - the sale is valid."

In our previous shiur, we saw that, according to the halakhah, a person may be coerced into giving their free-will consent (g’mirat da`at) to a binding agreement. Illogical? Unjust? Yes, but maybe realistic, too. In this episode we dig a bit deeper into the psychological, ethical, and even theological elements of this issue.

Source Sheet

"If they hang him from a tree until he agrees to sell - the sale is valid."

In our previous shiur, we saw that, according to the halakhah, a person may be coerced into giving their free-will consent (g’mirat da`at) to a binding agreement. Illogical? Unjust? Yes, but maybe realistic, too. In this episode we dig a bit deeper into the psychological, ethical, and even theological elements of this issue.

#13 – Coercion and Consent

Source Sheet

"If they hang him from a tree until he agrees to sell - the sale is valid."

That's absurd, right? Surely our freely given consent is absolutely required before we take on a legal obligation! Well, that's what we'd like to think. But the halakhah declares that there are times when we are pressured – or coerced – into giving our “consent” to an agreement… and even so, the agreement is binding upon us. Where's the justice in that? This episode begins a series in which we consider the not-always-clear line between coercion and consent.

Source Sheet

"If they hang him from a tree until he agrees to sell - the sale is valid."

That's absurd, right? Surely our freely given consent is absolutely required before we take on a legal obligation! Well, that's what we'd like to think. But the halakhah declares that there are times when we are pressured – or coerced – into giving our “consent” to an agreement… and even so, the agreement is binding upon us. Where's the justice in that? This episode begins a series in which we consider the not-always-clear line between coercion and consent.

#12 – Hallel on Yom Haatzmaut: B'rakhah or Not?

Source Sheet

Do you recite Hallel on Yom Haatzmaut? If so, do you say the b’rakhot? It makes a big difference. To recite a few Psalms is, well, to recite a few Psalms. But to recite them with b’rakhot is to declare that the recitation fulfills a religious obligation and that the day on which we mark Israel’s independence also celebrates an act of Divine redemption for the Jewish people. There's a great deal of theology and politics behind that statement. According to Jewish law, are we entitled - or forbidden - to make it? In this episode, we take a very quick look (hey - twelve minutes is not a lot of time!) at the halakhah behind the question.

Source Sheet

Do you recite Hallel on Yom Haatzmaut? If so, do you say the b’rakhot? It makes a big difference. To recite a few Psalms is, well, to recite a few Psalms. But to recite them with b’rakhot is to declare that the recitation fulfills a religious obligation and that the day on which we mark Israel’s independence also celebrates an act of Divine redemption for the Jewish people. There's a great deal of theology and politics behind that statement. According to Jewish law, are we entitled - or forbidden - to make it? In this episode, we take a very quick look (hey - twelve minutes is not a lot of time!) at the halakhah behind the question.

#11 – Prayer in Translation, Part 4

Source Sheet

In this episode, we read a responsum by Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, an eminent 20th-century Orthodox authority, on our question. Weinberg is candid enough to admit that the reformers who introduced vernacular prayer back in the 1800s had a powerful halakhic argument to support then. He indicates, as well, that the Hatam Sofer’s creative halakhic theory forbidding prayer in the vernacular (episode #10) does not really prove the reformers wrong. But he goes on to forbid the introduction of the vernacular into the synagogue service for other, non-halakhic reasons. It’s a good example of how supposedly “non-halakhic” considerations often influence the way that rabbis read the law. The question: which reading - the “reform” or the “orthodox” - is the better one?

Source Sheet

In this episode, we read a responsum by Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, an eminent 20th-century Orthodox authority, on our question. Weinberg is candid enough to admit that the reformers who introduced vernacular prayer back in the 1800s had a powerful halakhic argument to support then. He indicates, as well, that the Hatam Sofer’s creative halakhic theory forbidding prayer in the vernacular (episode #10) does not really prove the reformers wrong. But he goes on to forbid the introduction of the vernacular into the synagogue service for other, non-halakhic reasons. It’s a good example of how supposedly “non-halakhic” considerations often influence the way that rabbis read the law. The question: which reading - the “reform” or the “orthodox” - is the better one?

#10 – Substitutes for Wine in the Four Cups

Source Sheet

It’s a mitzvah mid’rabbanan, an ordinance of the ancient Rabbis, to drink four cups of wine at the seder on the night of Pesach. But must the four cups davka contain wine? It’s an important question, obviously, for people who can’t tolerate wine or simply hate its taste. It’s an even more serious question for those, like diabetics and alcoholics, who for serious health reasons must avoid this substance that we call “the symbol of joy.” Does the halakhah permit substitutes for wine in the four cups?

Source Sheet

It’s a mitzvah mid’rabbanan, an ordinance of the ancient Rabbis, to drink four cups of wine at the seder on the night of Pesach. But must the four cups davka contain wine? It’s an important question, obviously, for people who can’t tolerate wine or simply hate its taste. It’s an even more serious question for those, like diabetics and alcoholics, who for serious health reasons must avoid this substance that we call “the symbol of joy.” Does the halakhah permit substitutes for wine in the four cups?

#9 – Prayer in Translation, Part 3

Source Sheet

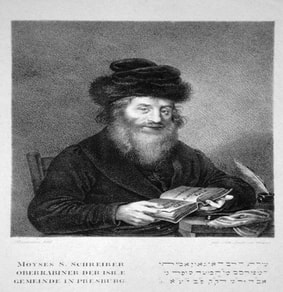

In the first episode of this series, we learned that the classical halakhah, as expressed in the Talmud and the codes (poskim) permits the recitation of the major parts of the worship service in the vernacular, "the language that one understands." In the second episode, we saw that the same is true - technically - for mikra megillah, the reading of the scroll of Esther at Purim. But medieval halakhic authorities objected that since we don't know the precise translation of every word in the megillah, it is better to read the scroll in its original language even if not everyone in the congregation understands Hebrew. In this episode, we'll see how Rabbi Moshe Sofer, the "Chatam Sofer" (that's him in the picture), a leading opponent of the early Reform movement, used a similar line of critique to develop a brand-new halakhic theory, claiming that despite what the Talmud and the codes tell us, synagogue prayer must be recited in Hebrew.

Source Sheet

In the first episode of this series, we learned that the classical halakhah, as expressed in the Talmud and the codes (poskim) permits the recitation of the major parts of the worship service in the vernacular, "the language that one understands." In the second episode, we saw that the same is true - technically - for mikra megillah, the reading of the scroll of Esther at Purim. But medieval halakhic authorities objected that since we don't know the precise translation of every word in the megillah, it is better to read the scroll in its original language even if not everyone in the congregation understands Hebrew. In this episode, we'll see how Rabbi Moshe Sofer, the "Chatam Sofer" (that's him in the picture), a leading opponent of the early Reform movement, used a similar line of critique to develop a brand-new halakhic theory, claiming that despite what the Talmud and the codes tell us, synagogue prayer must be recited in Hebrew.

#8 - Prayer in Translation, Part 2

Source Sheet

In shiur #7, we looked at halakhic texts that permit the recitation of the major rubrics of Jewish liturgy (k’riat Sh’ma and t’filah) in “the language that one understands.” In this installment, we trace the halakhah concerning the language of mikra Megillah, the mitzvah to recite/hear the scroll of Esther on Purim. We’ll see that, at least in theory, it is perfectly permissible to fulfill this commandment by reciting a text of Esther written in the vernacular.

But in practice…

Source Sheet

In shiur #7, we looked at halakhic texts that permit the recitation of the major rubrics of Jewish liturgy (k’riat Sh’ma and t’filah) in “the language that one understands.” In this installment, we trace the halakhah concerning the language of mikra Megillah, the mitzvah to recite/hear the scroll of Esther on Purim. We’ll see that, at least in theory, it is perfectly permissible to fulfill this commandment by reciting a text of Esther written in the vernacular.

But in practice…

#7 - Prayer in Translation, Part 1

Source Sheet

It's one of the earliest halakhic controversies between the Jewish religious reformers and their opponents.

Source Sheet

It's one of the earliest halakhic controversies between the Jewish religious reformers and their opponents.

#6 - Must Doctors Always Tell Patients the Truth?

Source Sheet

Must doctors always tell their patients the truth? That’s a complicated question. What does the halakhah say? That’s also a complicated question.

Source Sheet

Must doctors always tell their patients the truth? That’s a complicated question. What does the halakhah say? That’s also a complicated question.

|

#5 - The Kushya of the Beit Yosef:

Why Does Hanukkah Last for Eight Days Rather Than Seven? Source Sheet It’s one of the most famous kushyot (“difficulties”) in halakhic history: why does Hanukkah last for eight days when the miracle of the oil lasted for only seven days? Got a teirutz (an answer)? Compare it with those of our lineup of sages! |

#4 - The One and Only Mitzvah of Hanukkah and the Very Best Way to Fulfill It

Source Sheet

Forget (if only for a moment) the presents, the dreidel, the latkes, and the sufganiot. There’s only one actual mitzvah associated with Hanukkah: the lighting of the ner, the lamp or menorah. A simple act, right? Er, not so fast. We have a maḥloket for that.

Source Sheet

Forget (if only for a moment) the presents, the dreidel, the latkes, and the sufganiot. There’s only one actual mitzvah associated with Hanukkah: the lighting of the ner, the lamp or menorah. A simple act, right? Er, not so fast. We have a maḥloket for that.

#2 - The Ins and Outs of "Dwelling" in the Sukkah

Source Sheet

“You shall dwell in sukkot for seven days” (Leviticus 23:42). Really? How do I “dwell” in a sukkah – the same way that I live in my house?

Well, actually, yes.

Source Sheet

“You shall dwell in sukkot for seven days” (Leviticus 23:42). Really? How do I “dwell” in a sukkah – the same way that I live in my house?

Well, actually, yes.

#1 - The Mitzvah of Erev Yom Kippur

Source Sheet

We know that Yom Kippur (10 Tishri) is a big deal.

It turns out that Erev Yom Kippur, (9 Tishri) is a mitzvah in its own right.

Source Sheet

We know that Yom Kippur (10 Tishri) is a big deal.

It turns out that Erev Yom Kippur, (9 Tishri) is a mitzvah in its own right.